The information below will help you to understand the dynamic theory behind Limit Point driving.

During Part-Two and other advanced training courses some drivers are surprised at how fast some bends can be taken.

During the Part-Two test the examiner will be expecting you to make brisk progress on open roads, driving up to the speed limit where it is safe to do so.

The examiners guidance notes state:

'The candidate should not be regarded as having satisfactorily passed the part two test if they only demonstrate their ability to drive on normal roads at a low speed or in the lower gears.'

It's important to remember however, that in Part-Two and other advanced driving tests (including police and emergency driving tests) the ultimate aim is to drive safely, not to go as fast as you can regardless of the conditions, traffic density or view ahead. This said, many drivers go 10 or even 20mph below a safe and reasonable 'maximum' speed on clear open curves and bends.

On public roads the safe maximum speed will be determined by what you can see and what you might reasonably expect other road users to do. You must always drive at a speed that will enable you to stop well within the distance that you can see to be clear, however, his speed will always be much lower that the physical capabilities of your car. The reason that many drivers go 'too slow' is because they do not understand what their vehicle is capable of – or because they have driven too fast in the past and frightened themselves…

In order to improve your car control and safety in bends you need to understand about two key issues:

It's not possible to overcome the laws of physics. Some drivers go too fast into bends and up crashing – once you are committed at a speed that is too high there is no escape…

But some drivers crash on bends even though they are driving at a speed that is much slower than the speed that the car is easily capable of for the given situation..

When learning car control on racing circuits it's not uncommon for drivers with many years' experience of road driving to 'stab at the brakes' or spin off a bend at 50 mph with squealing tyres in a situation where the instructor could demonstrate the same bend safely and smoothly at 80 mph, perhaps with little or no tyre noise.

One of the key reasons that drivers 'panic' mid way through bends is because they are looking in the wrong place. During Part-Two and other training I often found that PDIs and ADIs had the car control skills necessary for bends, but starved their brains of information with 'short' observation.

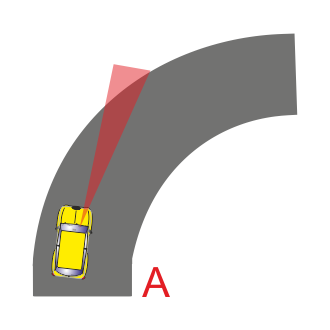

In illustration 'A' below we can see a driver using short observation. Often this driver will be looking at a sharp deviation sign, kerb, tree or something else directly ahead. This short observation will lead to one of two things.

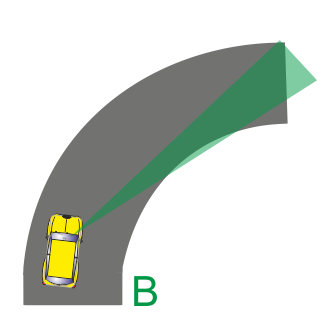

In illustration 'B' the driver is looking for the way out of the bend – extending his/her vision to the limit point.

Looking well ahead, and across the bend where necessary, will change your perception of speed and give your brain the information it needs to keep on course at a safe speed.

In reality, a good driver will keep his/her eyes moving, but with the primary focus being on the exit of the bend.

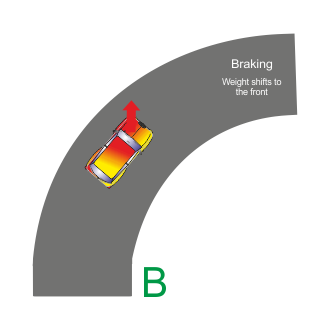

If you have ever had to brake hard you will have been 'thrown forwards' against your seatbelt as the weight of the car shifts forward onto the front wheels – effectively the back of the car tries to catch up with the front. This makes the rear of the car lift up and reduces the grip at the back wheels.

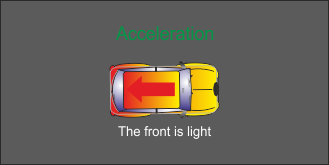

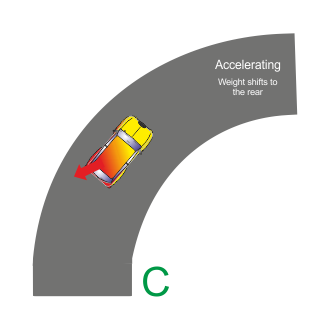

Likewise, if you have ever been in a powerful car that has accelerated hard you will have been pressed against the back of the seat (like in an aeroplane on take-off). This makes the front of the car lift up and reduces the grip at the front wheels.

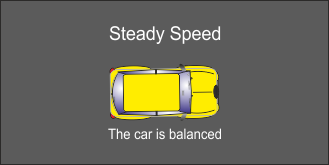

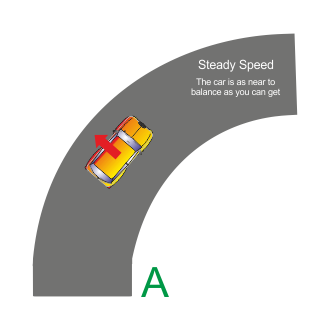

When the car is moving at a steady speed the weight is equally balanced on all four wheels.

Your aim is to keep the car as balanced as possible, trying to distribute the weight equally to all four wheels. Unfortunately, this is impossible going around a bend – so the secondary aim is to come as near as possible.

Illustration 'A' below shows that the weight is shifted to the outside of the bend (right or left) when the car is travelling at a steady speed. This means that the car will 'lean' on the tyres on the outside of the bend.

Illustration 'B' shows a car braking in a bend. In this situation most of the weight is thrown on to one front wheel. The dangers are that the rear wheels will lose grip as the back of the car is light, one front wheel will also have less grip and the car can spin around the other front wheel as it screams and screeches in pain!

Illustration 'C' shows a car that is accelerating around a bend. Here the weight shifts to one rear tyre.

When you brake or accelerate while in a bend your steering will not respond as you expect it to – the car can under-steer or over-steer.

Tyres only have a limited amount of grip available at any given time, the grip is shared between acceleration, slowing down and steering. By steering while braking or accelerating you are also asking more from your tyres than when keeping a straight steady course. If you are accelerating or braking there is less grip left for steering.

In extreme situations the tyres just give up and let go as it 'all becomes too much' for them! (The squealing noise that tyres make when on the edge is the equivalent of a human nervous breakdown.)

Use the 'limit point' method to keep a constant speed as you are going around a bend.

Remember SPG to help… Speed, Gear, Steer.

In normal road driving you should never enter a bend too fast – apart from anything else this would be likely to frighten your Part-Two or other examiner and lead to a failed test!

However, in the (hopefully) unlikely situation where you find yourself entering a bend to fast – of feel that you have entered too fast – don't be tempted to stab at the brakes.

It might sound odd but the best recovery will often be to gently increase your acceleration – this shifts the weight balance to the rear and minimises the risk of a rear wheel skid. And of course it is always essential to lift your eyes to look for the way out of the bend. Often simply lifting your eyes will be enough to change your perception of speed and reduce 'panic' enabling you to drive out of the bend smoothly.

Next: The Reading the road project